When trying to encourage a member of our team to step up to a challenge or task, their level of motivation to undertake that task can vary.

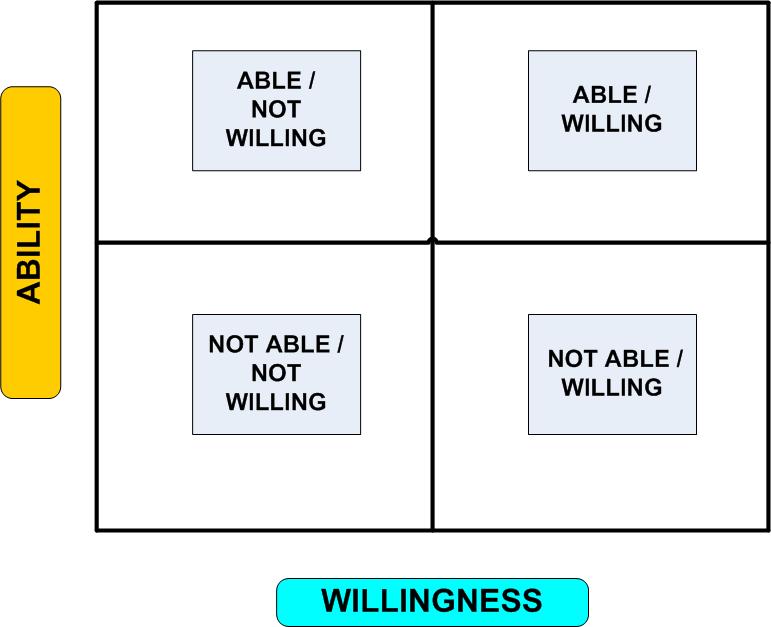

One quick way of looking at it is based upon whether they are ABLE – they have the skills and experience to perform the task, or if they are WILLING – they want to put forth the effort to do so.

One challenge here is we either make assumptions about either variable that may not be accurate or we fail to consider them at all and just hand off the task.

Here are the combinations to consider:

- Willing and able: Motivation should be High – delegate away!

- Willing but not able: Can’ t risk giving them a task without spending time getting them ready.

- Able but not willing: Examine why they are not willing. What can you do to influence them?

- Not willing and not able: Find someone else or accept the risks.

Victor Vroom, a sociologist and business school professor at the Yale School of Management, created the Expectancy Theory in the ’60s.

The theory attempts to explain why individuals choose to follow certain courses of action in organizations, particularly in decision-making and leadership. It argues that work motivation is determined by individual beliefs regarding effort/performance, relationships, and work outcomes.

For instance, if you ask a member of your team to make a presentation to the executive team for you while you are out of town on business, you might expect they would jump at the chance for the exposure and the opportunity to show their stuff, since the topic is one upon which they are very knowledgeable.

The employee, according to Vroom’s theory, will determine his/her motivation to perform this task as follows:

- (E→P): If I put forth the EFFORT, I can PERFORM the task of giving the presentation to the executive team. This judgment will have a lot to do with their comfort and ability as a presenter, their knowledge of the subject, etc.

- (P→O): If I PERFORM the task – making the presentation, there will be an OUTCOME for it. This could be exposure, influence on a topic the employee feels strongly about, etc.

- V: The VALUE the EMPLOYEE places on the OUTCOME.

Therefore, the “equation” looks like this: (E→P) x (P→O) x V = Motivation to perform the task.

So, from your perspective, this should be a plum assignment and opportunity for your employee. You believe they can do it based on you seeing her/him in action elsewhere, you believe anyone would want the exposure, so the value they would place on this should be very high – they should be very motivated to do this.

What you don’t know and the employee may be afraid to admit, is that before you got here, your predecessor asked them to do something much like this:

- They worked hard at the presentation but during its delivery, the meeting was interrupted with some challenging news.

- The attendees became less focused and started to throw out some unfair questions.

- The net of it was that the employee felt raked over the coals – it was not a pleasant experience!

This why you must analyze Expectancy Theory from the employee’s perspective and not project your values or confidence on to them. Just because you value something does NOT mean they will.

This tool and these questions can then be useful to assist you in preparing and moving a member of the team to higher levels of motivation.

How to Use This Tool

As you prepare for an interaction with an employee or colleague, break down the request you have for them and use the following questions to make better use of expectancy theory in reaching an agreement that will work for both sides.

PERFORMANCE

- Do I know what I want the employee to do?

- Is it important that the employee do it? If not, is it worth the effort?

- Can I communicate it so the employee understands it?

- If the employee does it, how will I be able to observe or confirm that it’s been accomplished?

(E→P) BELIEFS (IF I TRY, I CAN DO IT)

- What can I do to reinforce or increase the employee’s self-confidence?

- Can I get others (possibly my boss) to express confidence in the employee?

- What past successes of the employee can I cite? How does this task differ from past successes or failures? How can I help improve the employee’s ability?

- What support can I provide to the employee?

- How can I restructure the task so as to make it easier or more manageable, or at least to appear so to the employee? Can I break the performance change objective into subtasks? How can I provide positive feedback for the accomplishment of these subtasks?

- Am I a positive model for my employee?

(P→O) BELIEFS (IF I DO IT, I’LL GET SOMETHING FOR IT)

- What outcomes do I want to add?

- Have I considered internal as well as external outcomes?

- Are all the outcomes realistic?

- How much power do I have to make sure the outcomes happen? What can I do to make sure they happen? If I don’t have power over certain outcomes, what assurances can I get from those who do?

- Which positive outcomes do I want to emphasize or make more attractive?

- Which negative outcomes do I want to de-emphasize or eliminate?

- How can I convince the employee that the outcomes will happen? What past experiences of the employee can I cite?

V BELIEFS (WHAT I GET IS ATTRACTIVE OR OF VALUE TO ME)

- How can I influence the value the employee places on outcomes?

- How can I show that outcomes the employee perceives as negative are really not so bad, or possibly of positive value?

- How can I link outcomes that have low value to the employee with those that have greater value?

- What problem solving can I do with the employee to help reduce the probability that negative outcomes will follow?

FOLLOW-UP

- What ongoing interaction strategy can I use to maintain effort in relation to the performance objective? Can we set some follow-up times to stay on target?

- How will I reinforce the desired performance?

- What will I do if the employee doesn’t perform as desired?

Questioning Techniques for Making Expectancy Theory Work

When we’re trying to understand the employee’s perceptions/expectations on various parts of the Expectancy Theory model, we have to be sure to ask the right kind of questions. The previous series of questions for each phase of the model is structured for you, the leader, to reflect upon so you can ensure you have thought through things thoroughly on your end.

When you’re ready to get input from the employee, be sure to avoid closed-ended questions that can be answered “yes” or “no”. Employees may not want to admit they do not know something or that they have had a limited or perhaps unpleasant experience with a challenge.

You are not trying to put them on the spot, but only wish to increase their chance for success. So you need to probe further. The first thing is to ask open questions to find out about their experience.

Examples of lead-in word for open questions:

- What…?

- How…?

- Why…?

- Explain…

- Describe…

- Tell me about…

Examples of open-ended questions:

-

How have you handled this in the past?

-

Why is this a problem right now?

-

How do you plan to go about solving this?

-

What is your level of confidence in making this happen?

-

Describe the situation as you see it.

Encourage the employee to continue talking by using one of the follow-up probes from the list below:

-

“Tell me more.”

-

“Why do you say that?”

-

“For example?”

-

“Specifically?”

-

“What else should I know?”

Listen actively to the employee. When the employee has finished, summarize the gist of what you heard. Try to capture what is important to the employee. Begin your paraphrase/summary statement with a phrase like:

- “So, what I hear you saying…”

- “If I understand you correctly…”

- “Let me see if I have this…”

Then pause and wait for the employee to clarify, correct, or confirm.

I suggest you write up a summary of the key points from your conversation to ensure you have a clear record of your understanding.

Leave a Reply